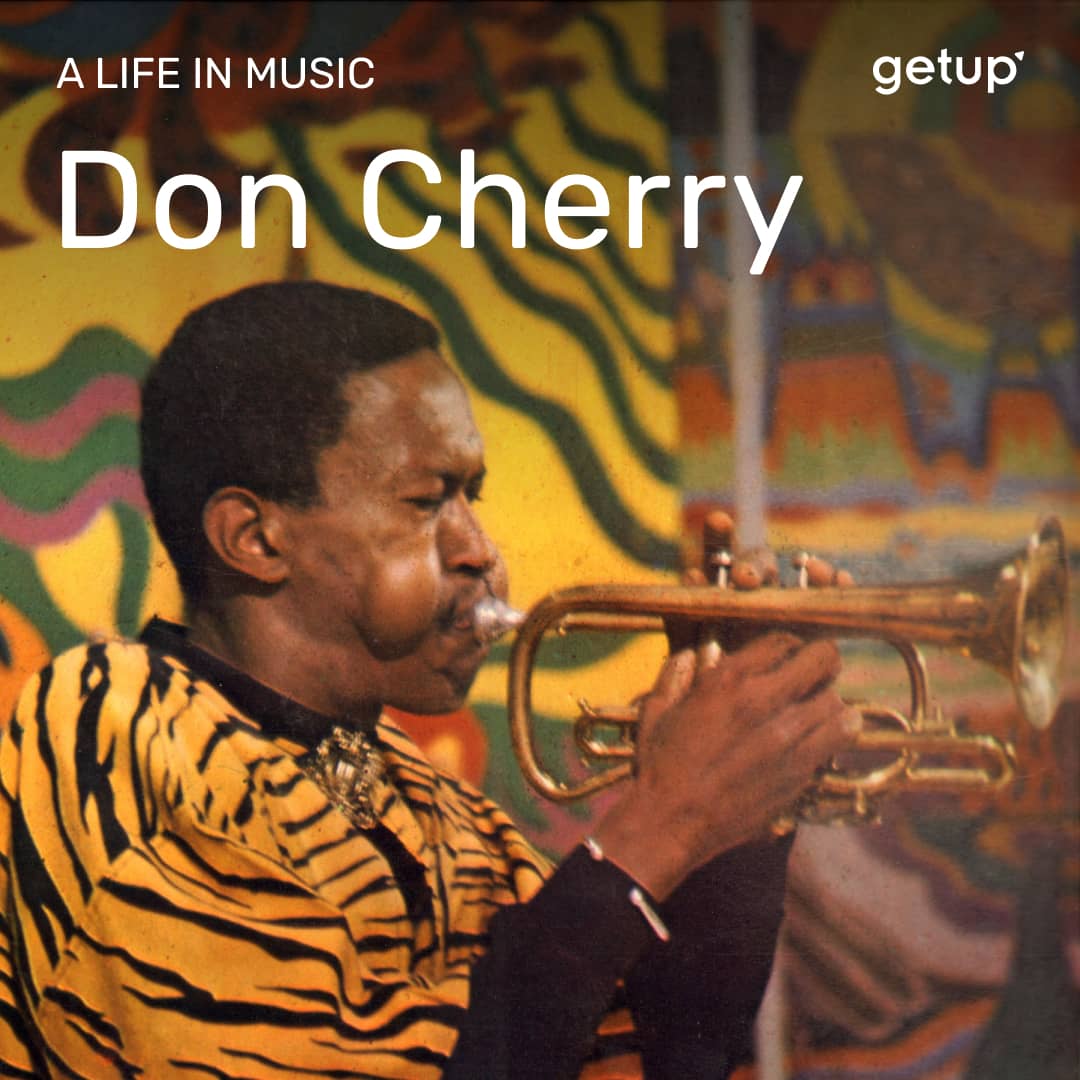

He played almost every kind of music, on every kind of instrument, from every continent. It was as though he was exploring not only the spectrum of Great Black Music (from blues to hip-hop), but all of world music, from India to Brazil. At a time when the catch-all term ‘world music’ didn’t yet exist, Don Cherry spent his whole life criss-crossing the globe in order to create his own folklore – the fruit of his wanderingly vast curiosity. As a result, his fan club counted everyone from Jimi Hendrix, Kristof Penderecki and Manu Dibango, to John Lee Hooker, Lou Reed and Alejandro Jodorowsky. Jazz pianist Carla Bley compared him to ET (‘he came from a different planet’) while the ambient electro artist FourTet included him in the pantheon of his favourite musicians of all time. Yet the trumpeter remains one of the 20th century’s most misunderstood jazz greats. Why?

This is, in part, explained by the fact that Don Cherry never played the industry’s game. Like the white rabbit in Alice in Wonderland, he escaped a category as soon anyone thought they’d got him pigeonholed. Just when we imagined him to be one of the major figures of free jazz, having featured on one of Ornette Coleman’s greatest albums of the early sixties, he took off to play with electroacoustic stalwart Jon Appleton and poet Allen Ginsberg. In the 70s it seemed as as though he’d set up shop creating spiritual jazz masterpieces (“Brown Rice”, “Hear & Now”, “Organic Music Society”), but then, before we knew it, he’d wound up on the ethereal German label ECM alongside his friends from the ‘new thing’ in the Old and New Dreams quartet.

We knew him as a trumpeter alongside legends like John Coltrane, Albert Ayler and Sonny Rollins, but we could also find him on flute, n’goni, or the organ with Codona – a fascinating trio he formed with percussionist Naná Vasconcelos and sitar and tabla player Collin Walcott. He was considered a (quasi) lone wolf in his projects with Terry Riley and Ed Blackwell, but then he also had supercharged adventures with the likes of Charlie Haden’s Liberation Music Orchestra, the Sun Ra Arkestra, and Swedish Bengt Berger’s Bitter Funeral Beer Band. He could talk to the Dagar brothers, exchange with cult dub poet Michael Smith, and embark on a project that pushed the limits of sophisticated pop on Home Boy, produced by free spirit Ramuntcho Matta.

The church of Don Cherry is broad. What he created was all his own, unique, precious, made up of sounds gleaned from the four corners of the world. His discography resembles the house of Ferdinand Cheval (a French postman whose life’s work was constructing a palace from stones, the design of which borrows from a myriad of cultures). Like the creator of that ‘Palais Idéal’, Cherry put imagination above all else: on one of his great records for Blue Note (Complete Communion, 1965), he composed a piece called ‘Elephantasy’. Years later, he would explain that the wordplay reflected his desire to leave the field open to surprises. Where John Coltrane praised supreme love, Don Cherry sought supreme surprise. More than a quarter of a century after his death (on 19th October 1995 in Spain), his sonic nomadism continues to amaze those of us who listen. It’s hard to find anyone who could be considered an heir to his legacy; what musician today can claim to be so profoundly eclectic? The question remains open, as does Don Cherry’s music.

.jpg)

.jpg)