At the beginning of the 1970s, the world was about to enter a new phase: the post-war rebuild had come to an end but new challenges were on the horizon. Gone were the thirty glorious years of a world that was growing at all cost. Now it’s hello mass unemployment. In the meantime, some good news for a planet that was on the verge or running itself to the point of destruction. The SALT agreements between the USSR and the United States marked the end of nuclear proliferation – a good start. The first Earth Summit was held in Stockholm under the patronage of the United Nations as a sign of growing ecological awareness. It was a starting point as the world began to plunge itself into the trap of globalised hyper-consumption.

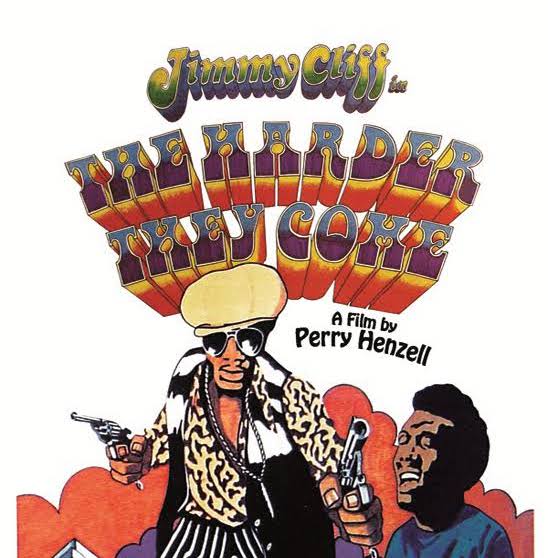

1972 – the Vietnam War was over, Latin America was in the grip of dictatorships, and there were a succession of coups d'état in Africa. In the United States, despite the civil rights movement, racism persisted. The sky was no longer red, but black was not yet mainstream. On the music front, David Bowie played the chameleon with Ziggy Stardust; Lou Reed released Transformer; Neil Young recorded the monumental Harvest; and Nick Drake came out with Pink Moon, the final chapter of his impressive trilogy. As for Jimmy Cliff, his hit song “The Harder They Come” heralded a wave of reggae that would sweep the world. In Africa, Fela started out a prolific decade with Africa 70; Bonga released his first collection that was to make music history; Hugh Masekela made his mark; Manu Dibango tested a formula that was to become a hit in 1973. They were among the first great voices of a continent that would still have to wait to emerge from the fog of post-colonial exoticism tinged with paternalism.

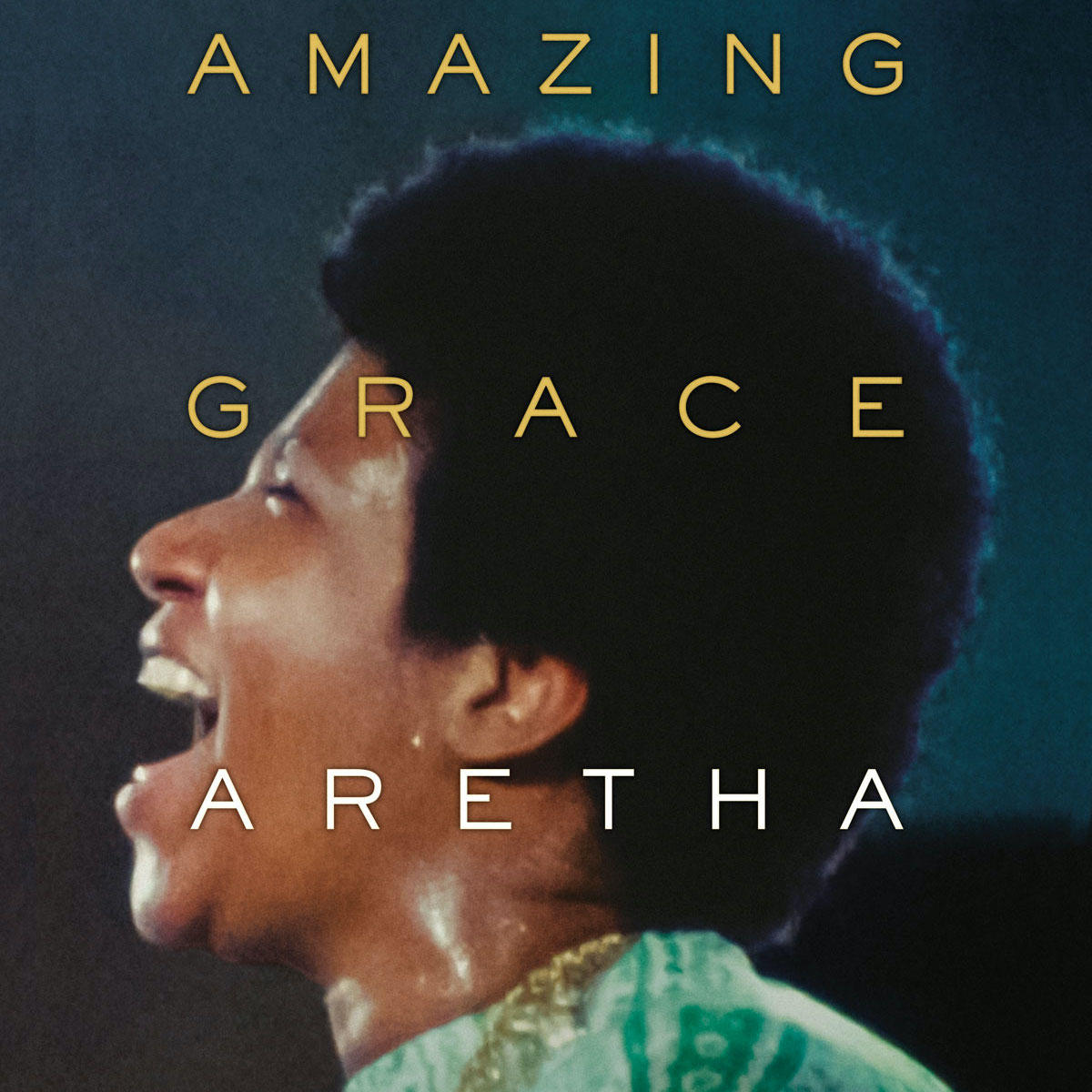

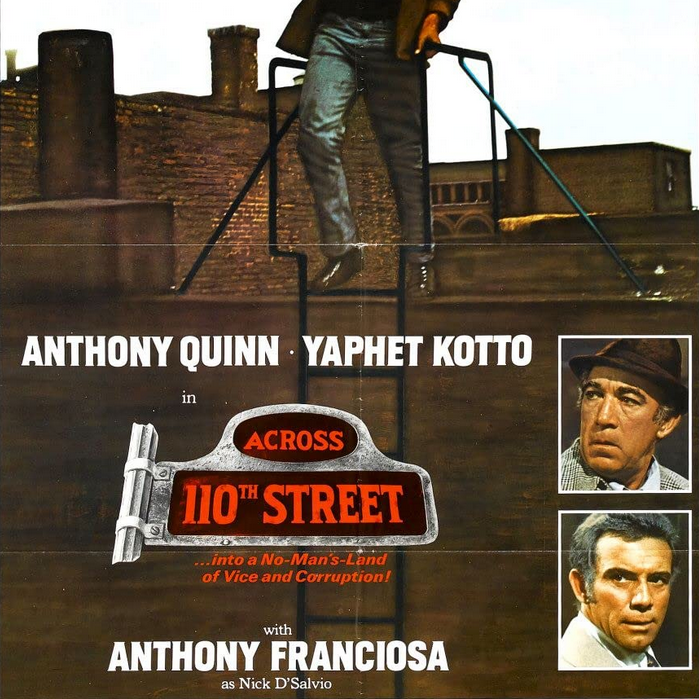

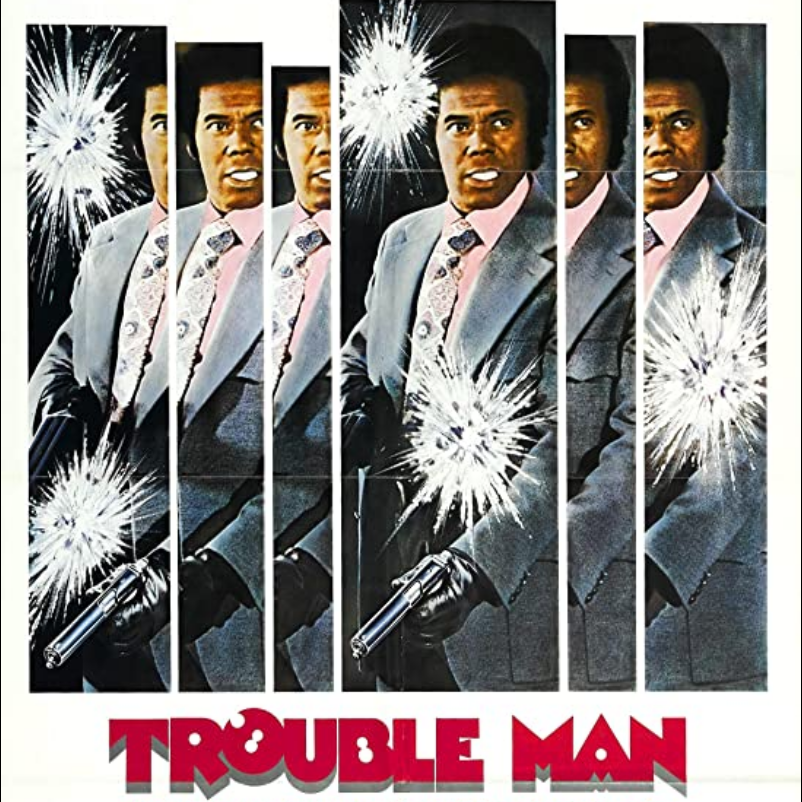

In the meantime, soul and funk dominated the ‘black’ music charts. “Let’s Stay Together” sang the Reverend Al Green – and he wasn’t the only father of soul to write romantic classics: Billy Paul’s “Your Song”, Michael Jackson’s “My Girl” and Bill Withers’ “Kissing My Love” are just three examples amongst many. Another trifecta of winners was Marvin Gaye, Curtis Mayfield and Bobby Womack, who were all enjoying the well known delights and successes of Blaxploitation. A special mention must go to Queen Aretha who was passing through Los Angeles for a session that forms the heart of gospel music: the eternal “Amazing Grace”. On the jazz front, the time for soul’s spirituality had come, something we can see with many of its greatest proponents – Cannonball Adderley released an ode to the signs of the zodiac and Michael White sang “The Blessing Song”. Archie Shepp opted for funk rhythms as he set his anger over prison conditions in the United States to music – the revolt in Attica prison was a cruel indictment. And Miles Davis – the electric version – was creating one visionary piece after another.

In South America both Ray Barretto and Joe Bataan perfectly embodied salsoul – an aesthetic embodiment of their mixed identities. Brazilians tend to acknowledge their differences, and not without style. Tim Maia, a long-time convert to soul funk, will have you sobbing your heart out; Jorge Ben combined these influences with samba, becoming an enduring superstar in his country. And Novos Baianos and Clube da Esquina – two collectives with numerous idiosyncracies – each recorded a collection that has since become an integral part of the country’s history and a legendary part of the history of world music.

1972 Rhythm & Soul Version

From Al Green to Fela Kuti via Miles Davis, Ray Baretto and Jorge Ben, let’s take a glimpse at 1972’s musical landscape – the rhythm & soul edition.

Share

.jpg)