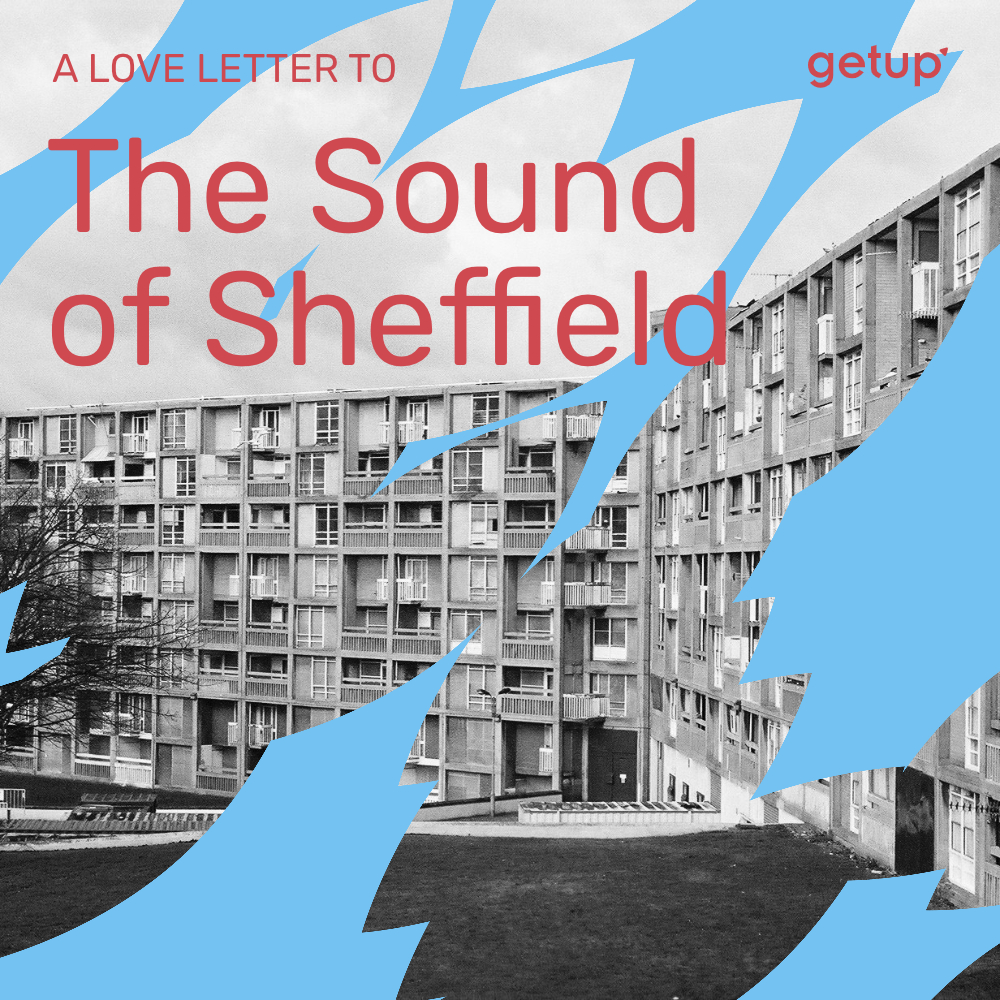

The summer of 1985. I’d decided to spend my holidays in Sheffield, having been invited there by an English friend from uni. My parents, who’d recently moved to the Atlantic coast, couldn’t believe it. Sheffield? After having been in Liverpool and Manchester the previous summer?! Arriving by bus to the South Yorkshire city, the most striking thing as you descend into a plain tucked between gentle mountains, are the cold chimneys of disused factories. At the heart of the city is a small record shop, FON, an absolute must for anyone strolling about the place. It was also the meeting place for young people who, 10 years after punk, were searching for a new musical revolution. Its walls resonated with the sounds of the city's radical creations, in the same way as the techno, electro, and house explosions had in Detroit and Chicago. I didn’t know it then but FON would later give birth to the label Warp – the epicenter of the British techno wave of the 90s – who signed Aphex Twin, Plaid, Autechre, and Boards of Canada. Amongst the homegrown talent, Sweet Exorcist brought together one half of Cabaret Voltaire, Richard H. Kirk, who has performed under other names including Sandoz, and has been associated with Richard Barratt alias Parrot. This prolific producer is on the New York label DFA under the alias Crooked Man.

This wave of new producers was part of the legacy of the historical alterations of the ‘70s, when steel and blast furnaces marked punk youth with a red iron, and where the metallic rhythms of the blast furnaces where their grandparents had worked sounded their industrial echo into music. The duo Cabaret Voltaire had a radical response to Suicide’s electronic rock’n’roll, whilst The Human League set to the synthes as if they were writing the soundtrack to a Philip K. Dick novel. When the band split up, two members left to found Heaven 17.

With Add N To(X) being enough of a generational crossover, industrial music has continued to influence bands well into the 2000s. A new wave of producers such as Kings Have Long Arms, Ross Orton, and Ben Rymer of Fat Truckers continue to play dirty synth riffs, with the duo I Monster leaning towards a more aerial electro-pop. When I returned to Sheffield for a second time the city hadn't changed, hadn't gentrified like Manchester, had managed to keep its simplicity as well as its sense of hospitality. It has even welcomed Londoners from Fat White Family to The Moonlandingz, a collaboration with The Eccentronic Research Council.

Over the years Sheffield has seen its share of post-punk groups (Artery, I'm So Hollow and, above all, the Comsat Angels) but the influence of northern soul and funk have been great on ABC’s pop, Clock DVA’s electro, Hula and Chakk, and Moloko – a group that musician Mark Brydon would later found with singer Róisín Murphy in a more pop vein. Toddla T also established themself in a bass music vein imbued with the quirks of Warp’s sound. As for Pulp, perhaps their forays into glam never quite rubbed shoulders with electro, but Jarvis Cocker’s weird dancing could only have come from Sheffield. This unique city’s philosophy can be summed up in the words of Future Loop Foundation: “Experimentation Begins At Home.” This home is precisely what matters to all its musicians, who remain loyal to it because they know what they owe it: cheap living, modesty, and a lack of pressure to create or – horror of horrors – follow a standardised format or a commercial imperative.

.jpg)

.jpg)