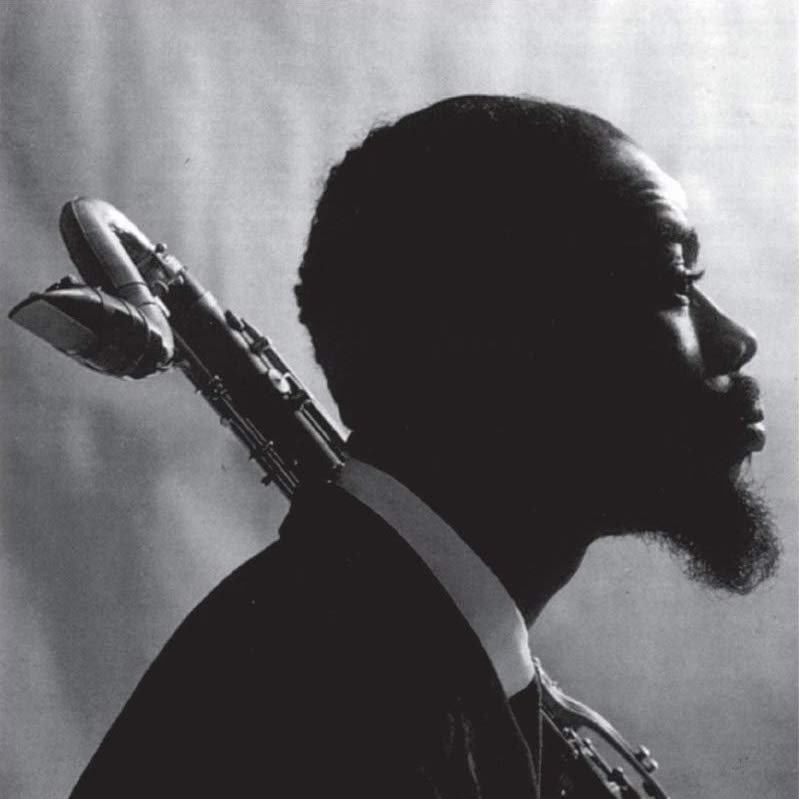

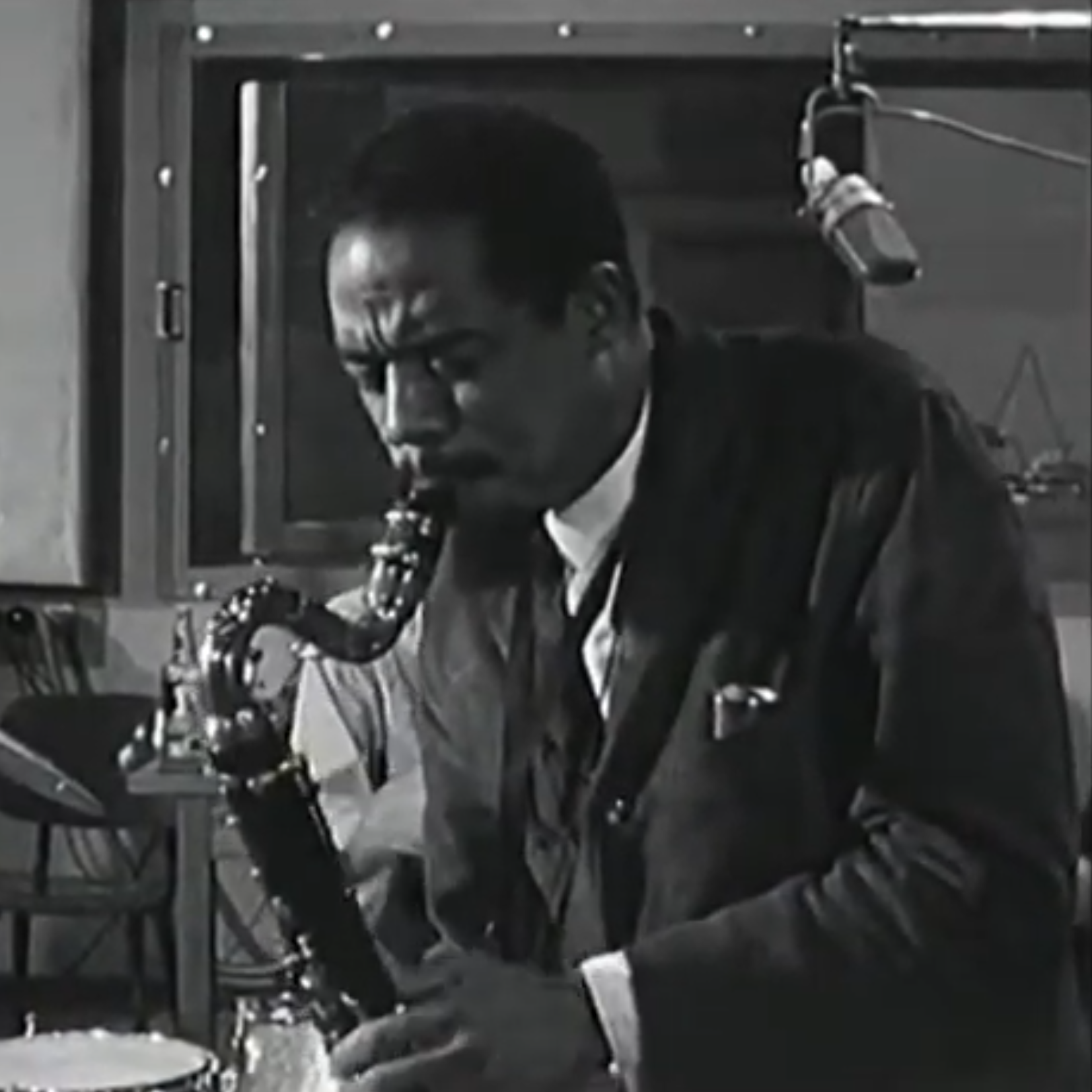

Miles Davis once said of the alto saxophonist, clarinettist, and flutist Eric Dolphy that he played as if someone was stepping on his feet. A witticism typical of Miles, but one which – fortunately – is not what history remembers most about the playing of this Los Angeles native. During a career that surfed between bebop and free styles, and sought to combine classical music with jazz, he was also the sideman to many a legendary frontman.

As a band leader, Eric Dolphy recorded nearly thirty albums (most notably two live volumes, At The Five Spot, as well as Outward Bound, Out to Lunch!, and Far Cry on which we find his faithful companion, the trumpet player Booker Little). But Eric Dolphy's discography as a sideman is just as extensive and says a lot about his propensity to move away from what might be considered ‘beautiful’ in order to reach the limits of free jazz – an avant-garde land where every rule might be broken, sticking to a time signature being chief among them. This style was to shake up the jazz critics, who were never very kind to Dolphy even as he became the great revelation of 1961. When I listen to Eric Dolphy playing in the bands of Charles Mingus, Chico Hamilton, Mal Waldron, John Coltrane, Max Roach and, of course, Booker Little, I can hear the liminality of two worlds colliding and sliding voluptuously against each other until only one remains. It’s a form of free style – playing with established conventions, forgetting them completely, unravelling themes, and improvising in order to embrace total freedom.

Until now, I’d never really been able to put my finger on why I’m so passionate about Dolphy's playing. So, I turned to the superb 1961 album The Quest, by pianist Mal Waldron, on which Dolphy plays the flute, among other instruments. I also listened to Dolphy playing with drummer Chico Hamilton (you can't miss an album like Gongs East!), saxophonist Oliver Nelson (The Blues and the Abstract Truth is a MUST, by the way!), double bassist Mingus (another must-listen, especially the live albums, Reincarnation of a Lovebird and Mingus Ah Hum, which are pure marvels) and, unsurprisingly, Booker Little – the trumpet player has an almost divine energy (one last must for the road, I think – OUT FRONT. I’ve written it in capital letters because it is one of my desert island discs). Can I also add the incredible Looking Ahead by saxophonist and flutist Makanda Ken McIntyre? Oh and just one more! Jazz Abstractions with pianist John Lewis, where he cultivates a fusion between baroque music and jazz.

So, after this meticulous dive into Dolphy's discography as a sideman, I understood that I was seduced by the roughness and the troubled character of his playing. This was the result of a dilemma: a desire to go further than Charlie Parker whilst at the same time wanting to plunge into ‘the shape of jazz to come’. A permanent in-between. Dolphy was this liminal musician, passing on a baton with distinct colours, a point of conjunction between aesthetics. ‘He is part of that sacred generation; one of the players who transitioned from the completely understandable work left to us by Parker, into the Unknown. This Unknown, which he passionately explored, is the crux of all his phrasing’, wrote François Postif in Jazz Hot in 1961. To which Eric Dolphy replied: ‘(...) You tell me that my hollering is anti-musical and that my squealing is an assault on the ear. All right, but even if everyone ran away every time I put my mouth on one of my three instruments, if no company would have agreed to record me, and if I had to starve to play what I feel – and that sound is exactly how I feel – well, I'd keep on playing that way against all odds.’ I’ll bet you that approach was what pleased a legend like Mingus, and all those who are able to make jazz rhyme with freedom.

.jpg)