“In The Pines” is the blueprint for the American folk song and has been used by numerous artists since the 1870s when it first came to light.

In this playlist, made up of 22 tracks from among more than 160 recorded variations, I have chosen to focus on the rich ‘pioneer’ period versions – and its derivatives – as they have defined contemporary interpretations, and as their evolution allows us to trace the history of American folk and pop music. Whilst seemingly unchanging and monolithic in appearance, the song’s plot often varies. A husband, wife or relative whose head was found stuck in a locomotive wheel, and whose body was never found. Women or teenage girls flee into the pine forest, which here serves as a metaphor for just about everything – sex, loneliness, misery, death. A train, ‘the longest ever seen’ can either kill or symbolise the flight of a lover.

The probable origins of “In The Pines” date back to the post-Secessional War era in the southern Appalachians, with early versions evolving from generation to generation via oral tradition. Lyrics have been added or modified depending on each performer’s inspiration or origins, even seeing “In The Pines" merge with a different song, “The Longest Train I Ever Saw”. The broad themes remain unchanged however – black, tragic, with murder and beheading, against a backdrop of macabre despair, distress, revenge, abandonment, loneliness and desolation. The refrain, ‘In the pines, where the sun never shines’, a couplet on ‘the longest train’ and a couplet on the decapitation are the three most staunch elements present.

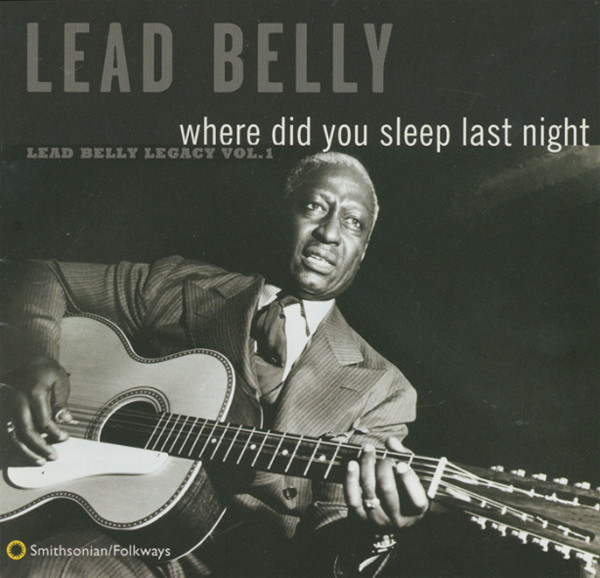

The first written version, made up of four verses, was set down on paper in 1917 by Cecil Sharp. The earliest sound recording dates from 1925 on a phonographic cylinder, and includes the first mention of the train. Over time, these four verses have evolved into more complex plots. The song has been performed by prisoners on a recording by ethno-musicologist John Lomax from the 1930s (Lead Belly was his assistant), by country pioneer Bill Monroe, by the psychedelic rock scene, by popular singers such as Connie Francis and Dolly Parton, by The Grateful Dead, Link Wray, Joan Baez, Pete Seeger, the actors from the TV show Bonanza, Dee Dee Ramone, and jazz saxophonist Clifford Jordan.

The most popular version is from Lead Belly's series of recordings from the 1940s, including “Where Did You Sleep Last Night”. This version has become fixed in the collective conscience thanks to Nirvana’s cover, Kurt Cobain having based his version on Lead Belly’s. Another benchmark version is Bill Monroe’s, a founder of Bluegrass in the 1940s, and a figure in the subgenre known as ‘high lonesome’, which uses a violin and yodeling to evoke the wind. A Cajun version entitled “Ma Négresse”, written by Nathan Abshire in 1966, developed the theme of “Black Girl”. That only confused people as it led comic book author Robert Crumb to falsely claim that “In The Pines” had French origins.

‘Hé, négresse! ayoù toi t'as partir hier au soir, ma négresse?’

(Hey, negress! Where did you go last night, my negress?)

The evocative power of Lynch-style images, the multi-layered character of the innumerable versions, and its evolution over time thanks to its many interpreters, all make this song a fascinating classic of American music.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)